shapeshifting across the tracks: a body in motion on the "east express"

on borders, landscapes, and survival during a twenty-eight hour train ride across Anatolia as a trans person native to these lands

The Doğu Ekspresi from Ankara to Kars takes twenty-eight hours, though in truth it felt longer, like we had become permanent residents of the iron corridor, whilst forming deep kinships with the other passengers. A journey both horizontal and vertical, sliding across the spine of Anatolia while also tunneling into the core of my own body.

The train drags us from the bureaucratic heart of the Republic toward its edges, where borders fray and tongues multiply. The regional accents blending into completely different languages, and facial structures slowly changing into different ethnicities. To move from west to east has felt like a binary myth unravel in real time.

Men and women here cannot sit next to each other on public transport in an effort to protect women from aggressions of masculinity, but in practice it limits the freedom that women have in order to travel on their own. I booked a women’s ticket, not out of identification, but out of survival. Choosing the women’s carriage allows me to sleep beside my partner, and perhaps more importantly, it protects me from the humid stench of male bodies pressed together: cock, balls, sweat, and the fear of violation saturating the night.

If you are wondering how I am able to travel as a trans masculine person in transition, especially to countries with conservative perspectives around queerness, I pick one end of the gender binary and wear it as my cloak. The simplest way to pick for me is whether someone will have access to my ID or not, for example in airports, bus journeys, and hotel check-ins are the spaces where my younger self is resurrected against my will. I surrender to my fate of being referred to as miss / she / her / deadname even if they are triple-checking that they got the right person in front of them. Any other situation, I have to prepare myself to use my deepened voice, use “masculine” slang and tone, and walk into the men’s toilet confidently and go past the urinals casually. It is a privilege that I get to shapeshift in this way so I can do what I love most and not have my transness become a limitation in how fully I live.

And yet, for reasons I can’t fully untangle, I feel strange calling this a privilege. Perhaps because it costs me something: the small rituals of erasure I know by heart. The shaving of my scarce beard, scraped off at a barbershop the day before. The softening of my jaw, the crossing of my legs, the deliberate modulation of my voice, scrunching of my shoulders to become a meek reflection of the man speaking to me, rather than standing tall with my own light. These performances are stitched hastily to a photo ID, where a younger version of myself still stares back. A girl who mutilated herself into boyhood, or so the society might interpret it.

The barber’s blade left the skin under my pubey moustache raw, smooth, almost luminous, uncovering the bald upper lip I haven’t seen since I started taking testosterone. Already, stubble breaks through, sprouting like stubborn weeds in the cracks of concrete. I catch myself in the reflection of the train window: a hunchback I once cultivated as a cloak with back arched to hide my breasts, now serves to conceal the flatness of my chest. The cloak shifts purpose as a wavering tool, like an exoskeleton that bends with my masking needs. A reminder that camouflage itself can be liberation practice, a way of surviving by remaking flesh into fabric.

After settling into our women-only cabin, the train conductor scanned my ID, his gaze sticking to my face as if testing its elasticity. A lingering stare that dissects, categorizes, pathologizes as Foucault called “the clinical eye”. A common question I get asked is “memleket neresi?” which means “where is your hometown?”. Although, it is not the same as asking “where are you from?” because this is associated with your roots. It is an enquiry into your ancestry and an answer to this loaded question can explain a lot about your views, family, beliefs, and in my case, an explanation to the bizarre appearance. A small probe for the story behind the mutation which I answered politely. He returned my card with no further comment, as though my body were an unsolvable riddle better left untouched.

The government’s surveillance does not need to be visible; it lives in my skin. I police my posture, keep my pitch higher, sit with legs folded modestly. José Esteban Muñoz describes survival as neither assimilation nor outright rejection but a third path: disidentification. A strategy of smuggling the self through hostile terrain, carrying queerness like contraband through checkpoints, letting misrecognition serve as armor. On this train, I disidentify with womanhood, with manhood, with every rigid box the public insists upon. I align just enough to pass, misalign just enough to remain myself.

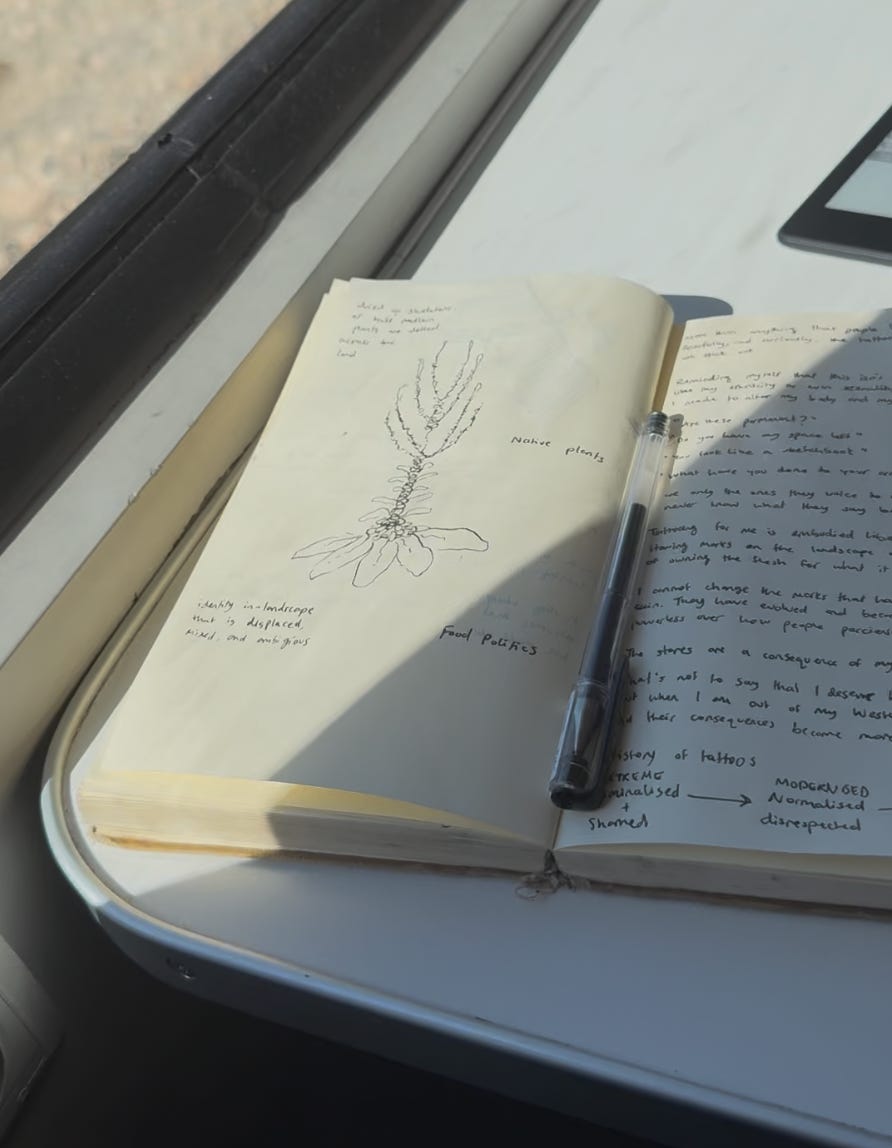

The land outside flickers in phases: yellow-brown grasslands stretched taut like dehydrated skin, dotted with the dried skeletons of mullein plants clawing upward toward a sun that has already abandoned them. They look like the remains of former selves, husks of lives sloughed off, left to stand as reminders of what has been shed.

With imperceptible slowness, hills rise. Ice crusts their surfaces, whitening the ridges, masculinizing the landscape. I watch as the grasslands thicken into mountains the way my voice thickened under testosterone: not all at once, but in tremors and gradual breaks. Snow peaks emerge like the first stubborn hairs pushing through the skin of my face, small stubbles announcing themselves against resistance. The land transitions in front of me, its shifts as incremental and miraculous as my own.

The train cuts through it all, a scalpel dragging across flesh-terrain, leaving scars that never fully heal. The rails are sutures binding east to west, but every incision is also a reminder that Anatolia’s body is never pure, never whole, never contained by the categories nationalism insists upon. Turkishness, womanhood, manhood, secularism, Islamism: all brittle shells, like mullein skeletons, too fragile to house the abundance beneath.

Robin Wall Kimmerer reminds us that relationship with land is reciprocal. The earth changes as we change; displacement is not a one-sided wound. Watching the terrain morph from grass to snow, I see my own shifting mirrored back to me. She teaches that the land is not inert matter but a body with whom we are in relation. Riding through Anatolia, I feel this reciprocity viscerally. The land mirrors my instability, and in turn, my instability mirrors the land. We are both fragmented, colonized, yet resilient in our refusal to collapse into a single identity.

By the time the peaks fully rise, I know the nationalist fantasy of a single Anatolia—one language, one body, one flag—is a lie. Streams cut valleys into mountains. Languages knot themselves into hybrid phrases. Prayer calls echo across towns while Atatürk’s portraits glare down, the secular father’s eyes unable to extinguish the murmur of Kurdish, Zazaki, Armenian ghosts. The land itself insists on multiplicity. It masculinizes and feminizes, dries and freezes, cracks and mends. It survives by becoming more than one thing at once. And so do I.

I think of Sylvia Wynter’s call to unsettle the category of the “human” itself, that colonial invention which excludes more than it embraces. If the human has always been weaponized, perhaps we should not aim to be recognized as men, as women, as citizens, but as something else entirely. As creatures of motion. As beings of reciprocity. As shapeshifters like rivers, like mountains, like trans bodies on trains.

To live as in-between is to live in constant motion, rattled by rails that demand you choose a direction, east or west, man or woman. But the land resists. The body resists. And so I carry the Doğu Ekspresi within me as a reminder that binaries can be split open, that landscapes can be read as flesh, that my body, too, is land, border, and transition all at once.

Thank you for reading my thoughts xxx

With love & devotion,

Ez